Netflix's CASSANDRA has a lot to say about 70s-era design, AI, women's roles at home, and the horrors of moving

The new sci-fi thriller updates The Hand that Rocks the Cradle and other wife-replacement suspense.

I’ve watched two updates on The Hand that Rocks the Cradle in the past month on Netflix. The first was a Megan Fox-vehicle, where a husband acquires a sexy robot to help with domestic duties when his wife and the mother of his small children goes into the hospital to receive a heart transplant (and is thus removed from the home, and much of the story). Everything about this film is so dumb and forgettable that I just had to look up the title again to write this sentence (Subservience).

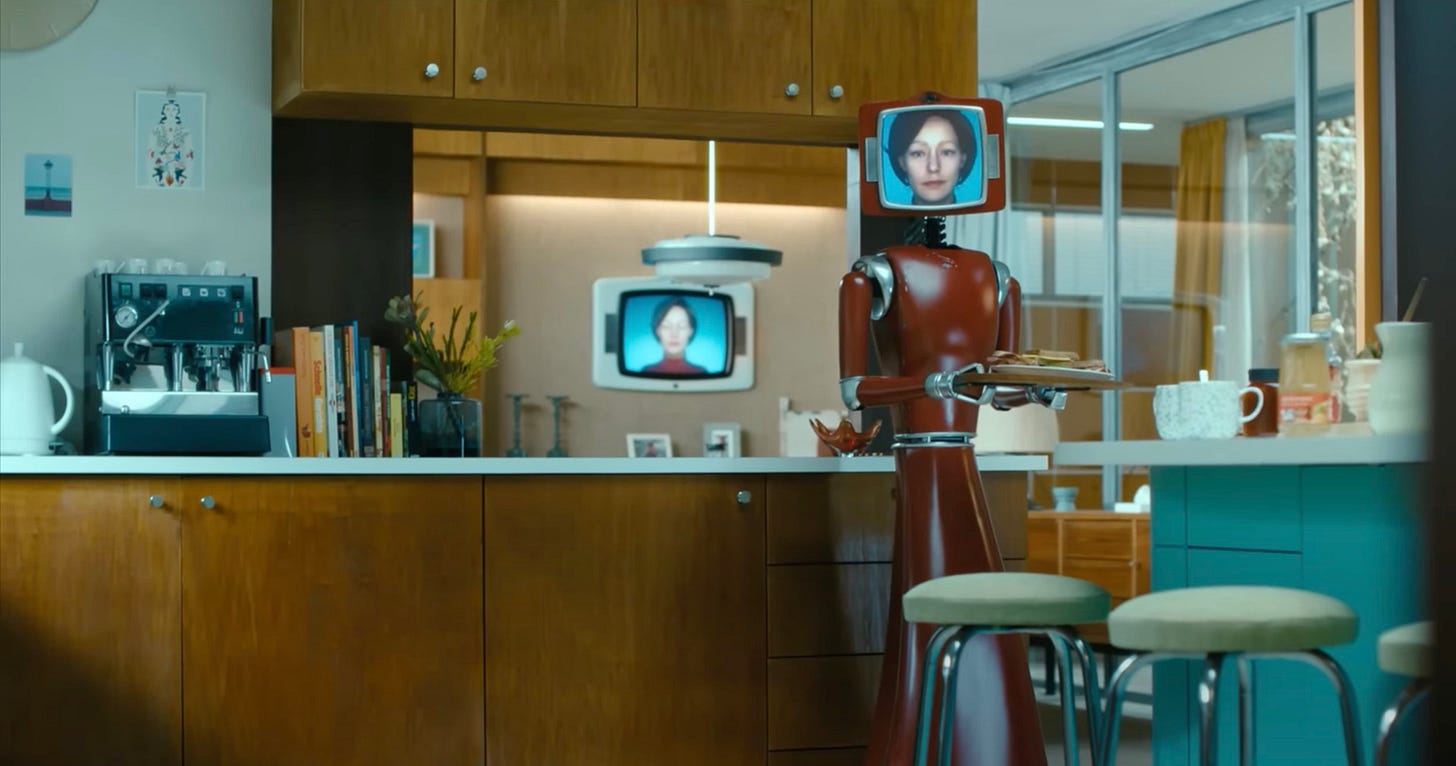

The other, much smarter take on the “wife-goes-crazy-when-she-gets-help” approach is Netflix’s new German (and German-language) production “Cassandra,” (director Benjamin Gutsche) about a young family (mom, dad, teen-aged son and grade-school daughter) who, after experiencing tragedy, move to a 70s era home in a new town — only to discover that the home is equipped with a whole-house robot system named Cassandra.

As much surveillance system as she is supportive technology, Cassandra (played by Lavinia Wilson) is — at least at the beginning — spirited and helpful, with a slightly subversive sense of humor. She’s kind of like Kitty from That 70s Show, if Kitty were subtly menacing and didn’t seem so harried.

SPOILER ALERT (skip next paragraph if inclined)

Who this Cassandra is and was, and more importantly, what she wants, drives the two main narratives. The first concerns the modern-day family grappling with the pressures of starting over as people with different desires and responses to grief, in a place increasingly more inhospitable to them. The second story line is a flashback where we learn about the real Cassandra, an actual woman whose personhood has been transferred from her cancer-riddled body at the most devastating time of her life into a full-house, manipulative surveillance monster who endangers the modern family physically and psychologically.

CONTINUE HERE

70s nostalgia and mid-century set pieces

The first sign of the coming terror is a classic horror movie trope: The home the family buys has some really bad juju.

It hasn’t been occupied since the original owners left, leaving behind some fun/quirky of-the-era 70s design elements like a room for watching slideshows, a bathroom with shiny black square tiling, a whole lot of dust and curvy, slip-covered furniture.

The 70s are actually quite trendy in the design world at the moment (see this Vogue story on the re-emergence of 70s design, from 2022), and this family of creatives (dad is an author, mom is an artist, the teenage son is a musician, the daughter is into theater) seems thrilled by it all.

A retro turquoise fridge! Formica countertops everywhere! Floating open staircases! Such good natural light from these floor-to-ceiling windows!

These people think they can get look of the period without inheriting all of the trauma embodied in the home’s walls.

They want the aesthetic and delight in the tech without being very self-reflective about how the home, with its bad energy, nefarious spaces, and meddlesome robot, is affecting their family.

They want the charm of Formica countertops and cute 70s cabinetry but forget to ask the question of whether humans still belong here.

They recline on rust-colored lounges and play charades (awkwardly) but tolerate children who trust tech more than their parents (relatable).

They delight in the pervasiveness of screens in every part of their life but only slowly ask themselves if this is a good idea.

I experienced a complicated joy at seeing these particular people move in these types of spaces again on TV. The architecture and stylishness of the rooms invite a high level of dreaming about what it could be like to live together happily as a family — think eat-in kitchens, media/gaming rooms, an indoor pool.

But with every changing set piece, these people want less and less to do with each other. Increasingly, the home reminds me of how modern life — with its ubiquitous tech — is set up to make us strangers to each other.

It all simmers and bubbles until the modern-day mom (played by Mira Tander) has had enough, everyone around her calls her crazy, and she is shipped off to the local mental health facility.

In that way, the series title “Cassandra” is as much a callback to the Greek prophetess doomed by Apollo to have her prophecies unheeded as the name of the robot. Cassandra is situation — someone sees the danger right there in the room, but no one takes her seriously.

managing it all

All of these dare-to-delegate stories (The Hand that Rocks the Cradle, Subservience, Cassandra) play off the reality that women who have accepted traditional roles within the domestic sphere often need help; but when they get that help, they can and will be replaced — as maidservants, as companions to their spouses, as confidants and comfort to their children, and as managers of their increasingly more complicated households.

I was really surprised about how much I cared about Cassandra and saw myself in her efforts to create structure for the entire family — the modern one she inherits as whole-house robot and her actual, real-life family, where she is forced to show up more robot-like with every fresh tragedy.

Even the robot’s wakeup song, “Guten Morgen Sonnenschein,” (“Good Morning, Sunshine”), a saccharine ditty from the 1970s, brought up for me the tenderness and rage that often comes with stepping into the role of devoted mother and household manager.

Its main chorus: “Good morning, good morning, good morning, Sunshine / This night was hidden from you / But you aren’t allowed to be sad.”

believability, bodily autonomy, betrayal

There are other compelling questions and themes floating throughout the six-episode series, like:

how men exert control over their wives’ bodies

what unintended consequences technological advancement bring for future generations

whether or not women are believed when they speak about their own experiences

how families respond to their children’s sexual identities

what parts of the human experience can safely be delegated to AI

But I was just as taken with Cassandra’s many satisfying visual and narrative nods to late 60s and early 70s-era horror films, like Rosemary’s Baby (the horror of growing life within a body), The Amityville Horror (the dangers of homes with bad predecessor energy), The Exorcist (a parent’s responsibility to expel the evils within their child), and The Stepford Wives (the gaslighting of a mother by her entire community)

The whole thing was riveting, surprising, scary, smart, and fun. Would love to hear your ideas if you get a chance to watch it!

P.S. Your loving this series might depend on whether you are capable of fearing an appliance. I sure can!